Unfair to expect angelic from mere humans: Fair Work

A custody officer fired for headbutting a door in frustration has won his unfair dismissal case. The Fair Work Commission found that the employer had a valid reason for sacking him. But the authority found that it was “unfair to apply the standards expected of angels to mere humans.”

In this article, we explore the events of this unfair dismissal case – Julian Rodney-Hansen v Ventia Australia Pty Ltd. We also look at another recent case that involved similar circumstances but ended with a very different outcome.

Custody officer dismissed for headbutting door

Julian Rodney-Hansen worked as a custody officer at Fremantle Justice Complex in Western Australia. He was employed by services company Ventia. On 28 April 2023, Mr Rodney-Hansen started his shift by remotely observing an inmate who was known to be difficult and a safety risk. The inmate had refused to comply with requests, leaving Mr Rodney-Hansen “stressed and tense,” Fair Work Commission documents report.

The inmate was also behaving in an abusive manner. He threatened to harm custody officers and commit suicide. He also began hitting walls, kicking doors and throwing hot coffee away. The inmate was performing handstands to put his head in the toilet, as well as stuffing his shirt in the toilet to flood his cell.

“I’ll slit your f**king throat”: Abuse escalates

Mr Rodney-Hansen was soon called to handle the inmate, and as soon as he arrived, he started copping abuse. When he tried to calm the inmate, he was told “fuck you fat c**t when I get out of here I’ll slit your f**king throat.” It was at that point that the inmate spat at the cell window.

Despite the continued abuse, Mr Rodney-Hansen persisted with trying to placate the inmate. He told him that there was no intention to keep him in custody overnight. But to this, the inmate shouted “f**k you f**king liar” and once again spat on the cell window.

Officer loses his cool

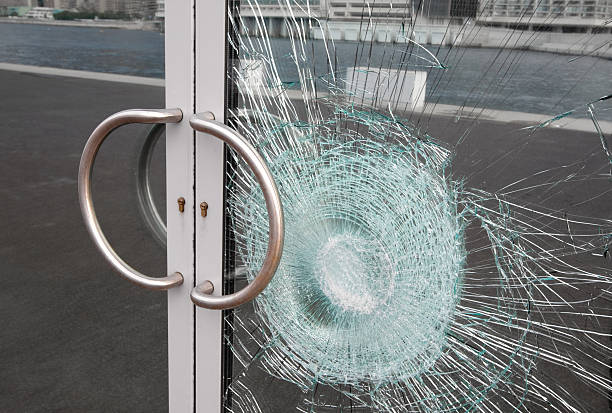

It was at this point that Mr Rodney-Hansen’s frustration boiled over. He admitted to the Fair Work Commission that he shouted “don’t you f**king listen” before headbutting the window of the cell door. He however maintained that the headbutt was not directed at the inmate and he knew that there was a door separating them. Mr Rodney-Hansen then left the area and entered the breakout room.

Later that day, he had a phone conversation with Ventia’s operations support manager. Mr Rodney-Hansen admitted that during this call he had told the manager that “it was a shame that he had headbutted the door rather than the [inmate’s] head.” However, he maintained that he was simply venting his frustration and did not intend to assault the inmate.

Ventia sent Mr Rodney-Hansen a show cause letter. The company alleged that he had purposely banged his head against the door as if to headbutt the inmate. Mr Rodney-Hansen once again denied that the headbutt was directed at the inmate. And he reiterated that he was rather “venting of his frustration against the door.” Mr Rodney-Hansen was subsequently summarily dismissed for serious misconduct over the incident.

Staffing concerns played into officer’s actions

Mr Rodney-Hansen contended to the Fair Work Commission that following the headbutt, he had removed himself from the situation. He also claimed that the incident “was limited to one very short interaction.” He admitted that his conduct was “wrong.” However, he felt that it was not sufficiently serious to warrant an immediate dismissal. And that it would have been more just to simply receive a warning.

He contended that staffing concerns should be considered a mitigating factor and accused Ventia of failing to provide a safe working environment. Mr Rodney-Hansen told the Fair Work Commission that a number of experienced staff had left in the months preceding the incident.

Fair Work Commission rules on unfair dismissal case

At Mr Rodney-Hansen’s unfair dismissal hearing, the Fair Work Commission found that the issue of understaffing “was perhaps the most significant factor” weighing on his mind. It was also accepted that given Mr Rodney-Hansen was of a bigger stature and male, he was “likely called upon to deal with a greater share of difficult [prisoners].” It was found that he would have been “on edge” prior to the incident.

The Fair Work Commission acknowledged that it was “likely that there were at least some inexperienced staff regularly working on the roster.” The lack of support for Mr Rodney-Hansen was found to have caused “serious safety ramifications.” This was because he worked in a “routinely dangerous and stressful” environment.

“Black and white” thinking of employer problematic

Ventia had argued to the Fair Work Commission that “the fact that [Mr Rodney-Hansen] did not physically assault the [prisoner] ought not weigh in his favour.” However, it was noted that when Mr Rodney-Hansen had assisted the prisoner later that day “he had a further opportunity to harm” him but resisted doing so.

The Fair Work Commission deemed that Mr Rodney-Hansen was “probably showing frustration rather than trying to intimidate.” And that a “distinction must be drawn between physical assault on a person and expressing frustration upon an inanimate object.” Ventia’s trying position, in which it did not want to accept inappropriate behaviour, was acknowledged by the Fair Work Commission. However, it was stated that “such a black and white position” was problematic.

Unjust to expect angelic standards with “threat of physical violence”

The Fair Work Commission made a point of stating that employees were “routinely subjected to abuse” at Fremantle Justice Complex. This includes “comments that would be unlawful if made to a person walking past on the street.” And that this all takes place with the “underlying threat of physical violence.”

It was acknowledged that Ventia had provided training and guidance to help its workers navigate these pressures. However, it was found that these measures were “imprecise instruments.” This is because they are trying to help workers “cope with human emotions which are incredibly complex.”

The Fair Work Commission stopped short of saying that Ventia was unwilling to prepare its workers for such pressures. However, it stated that “it may be unfair to apply the standards expected of angels to mere humans.” And therefore, “it may be necessary to take a very nuanced view of punishment for those employees who break the rules.”

“To be steadfastly opposed to making any allowance for genuine human frailties in very difficult circumstances where those frailties are routinely put to the test appears to me to leave no room for fairness in those – possibly rare – circumstances that may warrant a more considered approach,” the Fair Work Commission stated.

Prison officer loses unfair dismissal bid

Another recent unfair dismissal case involving a prison officer was Adam Heading v RR [2020]. Adam Heading had began working as a correctional officer at the Alexander Maconochie Centre in the Australian Capital Territory in 2007.

On 18 June 2018, Mr Heading and another officer were on duty in the management unit, where particularly volatile detainees are housed. On this day, a detainee got involved in a dispute with another detainee and refused instructions to return to his cell. It was then that Mr Heading placed the detainee in a bear hug. He wrapped his arms around the detainee below his shoulders and above his elbows. Mr Heading then lifted the detainee up and forced him to the ground, before landing on top of him.

Investigations into the incident concluded that Mr Heading used excessive force, resulting in the termination of his employment in February 2019. This decision was based on findings that Mr Heading’s actions constituted misconduct. And that his actions breached both the ACT Public Sector Correctional Officers Enterprise Agreement and relevant legislation.

Officer contests sacking via Fair Work Commission

In his unfair dismissal claim, Mr Heading argued to the Fair Work Commission that he had acted in self-defense and followed established protocols. He contended that his sacking was disproportionate to the alleged misconduct. He sought reinstatement to his position.

Mr Heading emphasised that leading up to the incident, he had been threatened by the detainee. He claimed that he had feared for the safety of other inmates. Mr Heading maintained that his actions were necessary to prevent potential harm. He, however, did acknowledge that he had made an error in judgement.

Key to Mr Heading’s defense is the contention that adequate training and support were lacking within the correctional system. He argued that this left officers ill-prepared to handle volatile situations.

Employer argues sacking was fair

In response to Mr Heading’s appeal, his employer contended that his use of force against the detainee constituted misconduct, warranting termination of his employment. It asserted that Mr Heading’s use of force was unreasonable, emphasising several key points.

Firstly, that he failed to employ de-escalation techniques, instead exacerbating the situation into a confrontation. Secondly, it claimed that Mr Heading used an unsanctioned and hazardous method, the “bear hug” technique, to subdue the detainee. This method, the employer argued, posed a significant risk of injury to both Mr Heading and the detainee.

The employer also noted that Mr Heading had a prior disciplinary incident involving the use of force. It argued that his actions contravened the Corrections Management Act 2007. The employer relied on CCTV of the incident to argue that Mr Heading failed to maintain a safe distance from the detainee. And that his aggressive demeanor escalated the situation unnecessarily. The employer maintained that officers are trained to maintain a safe distance from detainees and employ de-escalation techniques.

Ultimately, the employer argued that Mr Heading’s dismissal was justified given the severity of the misconduct and his previous disciplinary history.

Fair Work Commission makes decision

The Fair Work Commission analysed the CCTV footage of the incident. It was found that Mr Heading had not acted in self-defense or employed appropriate force, but rather that his actions were unprovoked and unnecessary. The Commission also found Mr Heading’s testimony contradictory and less credible compared to that of his employer. It was found that his actions, as depicted in the CCTV footage, violated the Corrections Management Act.

Mr Heading’s argument that he had received inadequate training was deemed to lack substantiation and contradicted evidence presented. Ultimately, the Fair Work Commission concluded that Mr Heading’s sacking was neither harsh, unjust, nor unreasonable. His unfair dismissal claim was therefore dismissed.

Conclusion to: Worker dismissed for headbutting door

Call our team at A Whole New Approach today. We have over 30 years of experience helping Australian workers take action via the Fair Work Commission. If you have experienced unfair dismissal, discrimination, bullying, a biased workplace investigation or any other workplace rights violation, including being forced to resign, we can help you make a claim.

But act fast, as you have just 21 days from the day of your dismissal to lodge a claim. We have helped over 16,000 Australian workers in every state and territory to make Fair Work Commission claims. And we offer a no win, no fee service with a free and confidential initial consultation.

Contact us today on 1800 333 666 to discuss your situation and how we can help.