Understanding Dismissal in Australia

Australia’s workplace laws are governed by the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth). Under s 386 of this Act, an individual is considered dismissed from their employment either when they have been dismissed at their employer’s initiative, or were forced to resign as a result of the conduct of their employer.

Dismissal for Misconduct

Individuals can be dismissed for engaging in misconduct in the workplace, as long as the reason for dismissal is valid. Dismissal for misconduct usually occurs when the employee breaches company policy or a reasonable and lawful direction lawful direction of their employer.

What might suggest the reason for dismissal is valid?

- All employees have faced the same consequences for the same unacceptable activity.

- The employee failed to follow the lawful and reasonable directions of their employer.

For example, in Woolworths Limited (t/as Safeway) v Brown, a butcher was dismissed after refusing to follow a lawful direction from his employer to remove his eyebrow ring at work.

Another example is Atfield v Jupiters Limited, wherein a casino employee was dismissed after breaching company policies against gambling whilst at work.

Furthermore, in Flanagan v Thales Australia Ltd, employees transmitting and accessing pornographic material on work email accounts were dismissed, as this was against company policy.

What might suggest the reason for dismissal is NOT valid?

Other employees have been treated with more leniency for the same issue

Do you feel this may be you? Contact us to learn more about how we can help you with your case of dismissal.

Dismissal Out of Work

Dismissal for Out-of-Hours Conduct

It is very rare that an employee’s out of hours conduct will give their employer a valid reason to terminate them. Private activities of individuals will usually be beyond the scope of employer regulation, unless the out of hours conduct is relevantly connected to the employment relationship.

According to Rose v Telstra, an employer may have valid reason to terminate the employee if the out of hours conduct involves one of the following circumstances:

The conduct can objectively be considered to cause serious damage to the employment relationship.

Some examples of conduct that may meet the above criteria may be:

Publicly criticising the company on social media

The conduct damages the interests of the employer.

The conduct is incompatible with the duties of the employee.

Criminal conduct in an employee uniform – the connection to employment is wearing a uniform, which potentially tarnishes the employers’ reputation.

Driving recklessly in a company vehicle – the connection to employment is engaging in dangerous behaviour while representing the employer, which potentially tarnishes the employers’ reputation.

Damaging work premises after hours – the connection to employment is being onsite when not working.

However, if there is no connection between the out of hours conduct and the individual’s employment, including something as serious as criminal offences, it is unlikely that the reason for dismissal by the employer would be valid.

Dismissal for Serious Misconduct

An employee may be dismissed for serious misconduct.

There are three elements for employee behaviour to amount to serious misconduct:

The conduct was wilful or deliberate and inconsistent with the employment continuing.

The conduct caused serious and imminent risk to the health or safety of a person

The conduct caused serious and imminent risk to the reputation, viability or profitability of the employer's business

These elements are required to establish serious misconduct as a cause for dismissal. It is not sufficient that the act or omission was intentional, but also that there was serious and imminent risk to a person or the employer directly as result of that conduct.

For example, in Lengkong v Bupa Care Services Pty Ltd t/a Bupa Morphettville, an employee failed to sufficiently report on an injured patient. Although this omission was wilful and inconsistent with employment, as it is a policy to do so, the omission was inadvertent and did not cause any risk to personal welfare or the employer’s interests.

Examples of serious misconduct:

Theft in the workplace

Fraud in the workplace

Assault in the workplace

Intoxication at work

Refusal to carry out a lawful and reasonable instruction that is consistent with the employee’s employment contract.

Contact us to learn more about how we can help you

If an employee has been dismissed for serious misconduct, the employer is not required to pay them notice (summary dismissal)

Just as with misconduct, the alleged serious misconduct must be a valid reason for dismissal. That is, the reason for dismissal must be ‘sound, defensible or well founded’.

If the employee alleges that they did not engage in the serious misconduct the employer is claiming they did, the employee may have an unfair dismissal case, especially if the employer is not able to provide any evidence of the alleged serious misconduct. For example, in Black and Santoro v Ansett Australia Limited, employees were dismissed due to them being alleged to have stolen alcoholic beverages from the company. However, the employer could not show evidence to prove this, and it was found that there was no valid reason for the dismissal. Black and Santoro also found that the standard of proof for serious misconduct must not only consist of ‘mere conjecture, guesswork or surmise’. That is, the employer cannot terminate an employee for simply assuming, without complete information, that the employee engaged in the alleged serious misconduct.

However, even if an employee has engaged in serious misconduct leading them to be dismissed, if the dismissal is objectively deemed a harsh response to the conduct, the employee may have a valid case for unfair dismissal.

The employer must prove that the employee engaged in serious misconduct on the balance of probabilities – that is, it is more likely than not. However, the stronger the allegations against an employee, the stronger the evidence the employer may need to provide to validate the reason for dismissal.

Moreover, the employer is not permitted to pursue illegal means to gather evidence against the employee. For example, in Walker v Mittagong Sands Pty Limited, this could involve the employer interfering with the employee’s personal property, which may be considered trespass to goods. Therefore, any evidence against found while engaged in illegal activity is thus not permissible in establishing a reason for dismissal.

We are ‘for the people,’ we fundamentally believe that it is the organisation that needs to change not the individual. We believe in breaking the cycle of toxicity for future generations and encourage systemic change through awareness.

Dismissal

Dismissal for fighting or assault

An employee may be dismissed for fighting or assault, which would usually be classified as serious misconduct. Firstly, physical violence is deliberate and not tolerated in the workplace (first element), and secondly, fighting or assault may threaten the health and safety of a colleague and may also tarnish the company’s business interests (second element).

More often than not, if an employee has engaged in fighting or assault in the workplace, the employer would have a valid reason to dismiss them. However, the occurrence of the alleged assaults must be proven to give valid reason for dismissal.

For example, in Dewson v Boom Logistics Ltd, it could not be proven that the dismissed employee actually committed the alleged assaults, and thus their dismissal was not for a valid reason.

However, the reason for dismissal may not be valid if an extenuating circumstance is present in the situation. If so, the employee’s dismissal may be considered harsh, unjust or unreasonable, meaning they may be eligible to make an unfair dismissal claim in the Fair Work Commission (which can be lodged with the assistance of representation – call 1800 333 666).

An extenuating circumstance for an employee, meaning that they were not validly dismissed, may include:

They were acting in self-defence

They were acting in self-defence

They had a long period of service without prior issues

Whether the breach was a single incident or recurring

Whether the breach was a single incident or recurring

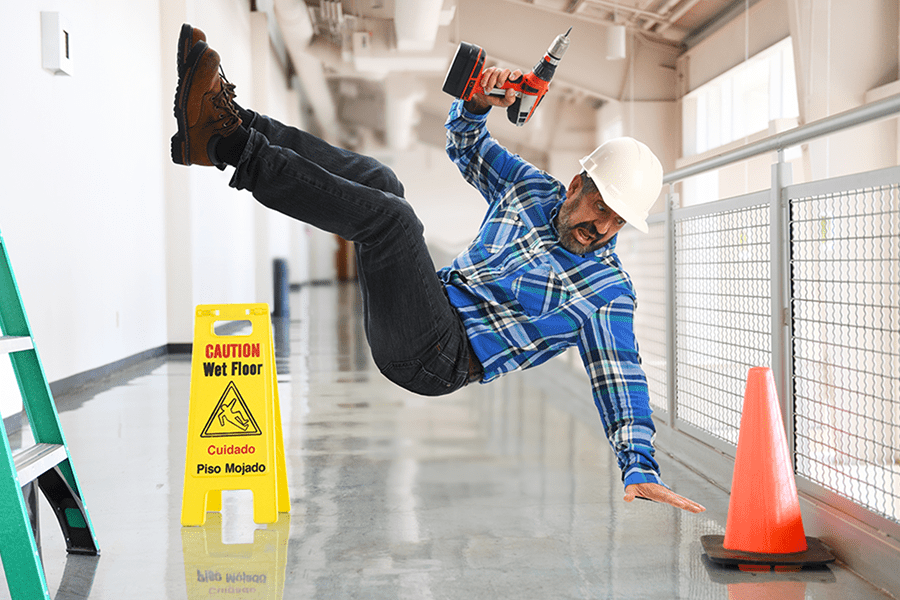

Dismissal for affecting the safety and welfare of other employees

An employee may be dismissed if the employee’s conduct or capacity affects the safety and welfare of other employees. This is usually classified as serious misconduct.

An employee can be dismissed on this basis if their conduct was deliberate or wilful and posed a risk to the health and safety of other employees. Usually, Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) standards will have been breached.

If there has been a breach of safety, the dismissal will likely be valid.

The following factors may be considered by the Fair Work Commission if an unfair dismissal application is made to determine whether there was in fact a breach of safety:

The seriousness of the breach

The company policies on safety procedures

The amount of OHS training the employee received from the employer

Whether the employee was a supervisor, and thus entrusted with higher responsibility to lead other employees by example.

Dismissal for Performance

An employee can be dismissed if there are serious issues with their performance, which includes ‘factors such as diligence, quality, care taken and so on’.

If the performance of an employee has been substandard and unsatisfactory, the employer should provide the employee with a warning (written or verbal) before terminating them. However, contrary to popular belief, there is no specific number of warnings an employee must receive before they are dismissed.

Ultimately, an employee dismissed for performance may have a potential unfair dismissal claim if:

They were not warned about their performance being unsatisfactory and given an opportunity to improve prior to their dismissal

The warning did not indicate what aspect of the employee’s performance was deficient and requiring improvement.

The warning did not clearly indicate that the employee’s employment may be at risk if they fail to improve their performance.

A warning issued to the employee was not consistently applied amongst all employees engaging in the same conduct. For example, regarding smoking or late attendance.

The warnings issued were predetermined prior to the disciplinary meeting, thus suggesting that the outcome of the meeting had already been decided prior.

Moreover, is not enough for an employer to terminate an employee merely because they have lost trust and confidence in the employee’s ability to perform their role. Just like with all other reasons for dismissal, the employer must have adequate reasoning and evidence for their assertion that the employee is now unable to perform their role sufficiently.

An example of how trust and confidence can be destroyed, and the dismissal thus valid, is dishonesty. In Streeter v Telstra Corporation Limited, an employee was consistently dishonest in a disciplinary interview, claiming that the events in question had not taken place, though later conceded that they had. The employer was deemed to have reasonably dismissed the employee because their dishonesty meant that they could not be trusted to be honest in the future. Another example is that of Woodman v The Hoyts Corporation Pty Ltd, in which an employee was dismissed for stealing and dishonestly denying it. Although the theft was negligible, the dishonesty involved meant that trust and confidence in the employee was lost.

Dismissal for Incapacity

An employee may be dismissed if they are not able to perform the inherent duties of their position (‘incapacity’)

Only the ‘substantive position or role’ of the employee is to be considered in assessing whether the employee is incapacitated. That is, for the employee to be dismissed on this basis, they must be unable to perform the duties for which they were employed to fulfil. However, if the employee is unable to fulfil duties have been altered, or they have been required to temporarily fulfil another position, this inability to perform outside their ordinary position is not a valid reason for dismissal.

However, if it is unlikely that the employee would return to work in the short or medium term after three months’ of absence, then the employer may validly terminate the employee, requiring labour.

Ultimately, an employee dismissed for incapacity may have a potential unfair dismissal claim if:

The employee was temporarily ill or injured, and as a result was absent from work for up to three months continuously or in total over a 12 month period. Under the Fair Work Act 2009, an employee cannot be dismissed for temporary absence for illness or injury. This does not constitute incapacity.

The employee was temporarily ill or injured, and as a result was absent from work for over three months, but indicated that they expected to return to work in the short or medium term.

Their incapacity was in relation to duties they were not hired to perform. These may be ‘modified, restricted duties’ or a ‘temporary alternative position’.

Dismissal for Abandonment of Employment

An employee may be dismissed for abandoning their employment. An employee is deemed to have abandoned their employment if they stop attending their workplace, without an explanation or valid excuse.

In such circumstances, dismissal at the employer’s initiative is valid because in not attending work, the employee has demonstrated that they are unwilling or unable to substantially perform their employment obligations, as per their contract. Even though the employer is choosing to terminate the employee, the conduct of the employee is the one that ends the employment relationship as they are evincing that they no longer intend to be bound by their contract.

Ultimately, the legal test for whether an employee has abandoned their employment is if the employee’s conduct would convey to a reasonable person, in the employer’s position, that they are renouncing all or part of the employment contract.

Redundancy

An employee may be made redundant from their employment, essentially meaning that they are no longer required in their employment.

A redundancy is considered genuine, and therefore ineligible as an unfair dismissal claim, if three requirements are met.

- The employer no longer required the person’s job to be performed by anyone because of changes in the operational requirements of the employer’s enterprise.

- The employer has complied with any obligation in a modern award or enterprise agreement that applied to the employment to consult about the redundancy.

- The employee could not have reasonably been redeployed, either within the company they already worked for, or for an associated entity of the employer.

If one of these three requirements are not met, the employee may be able to pursue an unfair dismissal claim through the Fair Work Commission, alleging that their redundancy was not genuine and should thus amount to an unfair dismissal.

However, if an employee commences an unfair dismissal claim and the employer believes that the redundancy was genuine, the employer is entitled to make a jurisdictional objection to the employee’s claim. If it is subsequently found by the Fair Work Commission that the redundancy was genuine, the Commission will not be empowered to hear to the unfair dismissal claim. Conversely, if it is found that the redundancy was not genuine as per the above requirements, the employee’s unfair dismissal claim may be conciliated (or eventually determined) by the Fair Work Commission.

Unfair Dismissal

Elements that may point towards the dismissal being unfair:

There was NOT a valid reason for the dismissal based on the employee’s capacity or conduct.

The employee was NOT notified of any issues with their capacity or conduct.

The employee was NOT given an opportunity to respond to any alleged issues with their capacity or conduct.

The employee was unreasonably NOT allowed to have a support person in any dismissal-related discussions

The employee was NOT warned about any unsatisfactory performance before being dismissed on that basis.

The size of the employer’s enterprise would NOT likely affect the dismissal procedures relating to the employee.

• The absence of human resources managers in the employer’s enterprise would NOT likely affect the implementation of dismissal procedures relating to the employee

Contact us to learn more about how we can help you

Elements that may point away from the dismissal being unfair:

There was a valid reason for the dismissal based on the employee’s capacity or conduct

The employee was notified of any issues with their capacity or conduct

The employee was given an opportunity to respond to any alleged issues with their capacity or conduct.

The employee was allowed to have a support person in any dismissal-related discussions.

The employee was warned about any unsatisfactory performance before being dismissed on that basis.

The size of the employer’s enterprise would likely affect the dismissal procedures relating to the employee.

The absence of human resources managers in the employer’s enterprise would likely affect the implementation of dismissal procedures relating to the employee.

Contact us to learn more about how we can help you

Additionally, not everyone is eligible for an unfair dismissal claim.

- An employee must meet the minimum employment period. For a company of over 15 full-time or part-time employees (casuals are not included in this number), the minimum employment period is 6 months. For a company of less than 15 full-time or part-time employees, the minimum employment period is 12 months. This employment period is continuous, meaning that there must be no breaks in the employment due to earlier resignation or dismissal. Absences

- An employee must not be employed by a State government employer, which includes State-run schools, hospitals and the public service. However, the matter may still be pursued through the State’s industrial relations system.

- The employee was dismissed by way of a genuine redundancy, as the reduction in the operational requirements of the enterprise reasonably justifies dismissing the employee.

Nevertheless, if the employee believes that their redundancy was not genuine and was rather targeted at them for some reason (for example: a personal conflict with a manager; discriminatory reasons; reporting sexual harassment), the employee may have a valid unfair dismissal claim – especially, for example, if they were the only one made redundant or were not offered any redeployment options that were readily available.

- If an employee is employed on a casual basis, they are ineligible for an unfair dismissal claim unless they are be employed on a ‘regular and systematic basis’ and had a ‘reasonable expectation of ongoing employment on a regular and systematic basis’. In other words, the employee may have had consistent shifts each week and expected this to continue.

Per Ponce v DJT Staff Management Services Pty Ltd T/A Daly’s Traffic,[1] regular and systematic employment may be established where the following two conditions are met:

- The employee was offered suitable work at times that they were known to be available.

- The employee was offered and accepted the work on a regular basis, more often than what could be considered rare or occasional.

- An employee must not be an independent contractor. However, contractors may pursue a General Protections Application (Form F8) in relation to their dismissal, regardless of their contract length.

A dismissed employee has 21 days after their dismissal becomes effective (ie. the day following their last day of employment) to lodge an unfair dismissal claim with the Fair Work Commission. For assistance with this process and to seek representation, please call our specialised team at any time on 1800 333 666.

Unlawful Termination

Employees who are not covered by the national workplace system & are ELIGIBLE for an unlawful termination application:

State government employees (only in NSW, Qld, WA, SA & Tas)

Local government employees (only in NSW, Qld & SA)

Employees of non-constitutional corporations in WA (including employees of sole traders, partnerships & trusts).

Employees who are NOT ELIGIBLE for an unlawful termination application:

Employees who are able to make a General Protections application

Contractors

Employees who resigned (and were not forced to resign by the conduct of their employer)

Employees under a contract for a specific time, task or season (and were dismissed after this time, task or season ended)

Trainees employed for a specific time (and were dismissed after this time ended).

Contact us to learn more about how we can help you

These unlawful reasons are as follows:

Temporary absence from work because of illness or injury

Trade union membership or participation in trade union activities outside of work (or during work hours at the employer’s consent)

Non-membership of a trade union

Seeking office, or acting or having acted in the capacity of, a representative of employees

• Absence from work during maternity leave or other parental leave

Temporary absence from work for the purpose of engaging in a voluntary emergency management activity, where the absence is reasonable having regard to all the circumstances

The filing of a complaint, or the participation of proceedings, against an employed involving alleged violation of laws or regulations or recourse to competent administrative authorities

A discriminatory reason, unless the reason is based on the inherent requirements of the particular position of employment.

Communication of Dismissal

In any circumstance, the dismissal – in the form of a dismissal or a resignation – must be clearly communicated. There must be a separation of the employee from their employment.

The employee should also be given a reason for which they are being dismissed.

Restore Your Sense of Self

If you feel as though your confidence has taken a hit, or defeated as though it will be just as bad everywhere and exhausted from battling the bullies. Know that you are not alone, it is not your fault and you can recover from this. We are here to help you restore your sense of self, overcome this toxicity and move forward.

Have a Question? Get an Answer.

Contact Details

- 1800 333 666

- mediate@awna.com.au

- Australia Wide

- 7 Days a Week