Mental health and workplace stress

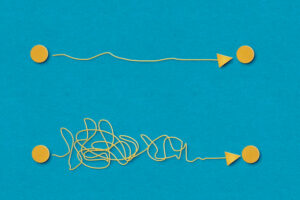

In Australian workplaces the term “abandonment of employment” strikes a particularly strong note in a era of increased mental health concerns and workplace stress. For employers, it raises concerns of operational disruptions. While for employees, a breakdown in communication, often rooted in personal tragedy or misfortune. Lets embarks on a journey through the legal forest known as the Fair Work Act 2009. While shedding light on the often heartbreaking personal stories that employees tell. At AWNA we gets these enquiries and dismissals daily.

A Human Perspective

Fatal Car Accident

John, a dedicated accountant at a leading Melbourne firm, was known for his punctuality and commitment. His life, neatly seperated into work and family, took a tragic detour with a fatal accident that claimed his wife, Lisa. As days morphed into weeks, John’s vacant office chair wasn’t just an emblem of his absence but a stark reminder of life’s twist and turns.

While colleagues murmured condolences, Human Resourses took notes of the accumulating leave days. John’s grief, increased depression and family resposabilites were not considered. The employer knew what was wrong, and where he was and still dismissed him for not keeping in touch with his employer. One of the comments by the employer was their concern was when he comes back to work he will make everybody feel sad.

Chemotherapy Reaction

Sarah, with her positive spirit, had been the cornerstone of her team, even as she battled breast cancer. When a chemotherapy session led to unforeseen complications, she was confined to a hospital bed, surrounded by beeping machines, not the familiar hum of her workstation.

Her absence, though rooted in a life-threatening medical challenge, quickly snowballed into a managerial concern. This story underscores the dilemma of Employers needing to function at their best versus human compassion. For Sarah’s teammates, her empty desk was a constant reminder of the unpredictable nature of life; for management, it was a potential case of abandonment of employment. Its easier for the employer to look forward with a new employee. Than look back and deal with the past employee.

Mental Health Challenges

Emily’s battle was silent. As depression tightened its grip, she found solace in isolation. The once-enthusiastic graphic designer saw her creativity stifled, not by a lack of inspiration, but by an overwhelming mental burden. Employees are not communicating with their employer like they used to or they should.

Emily struggled with twin challenges: the debilitating weight of her depression and the looming issue of abandoning their job. Mental health remains one of the most overlooked reasons for prolonged absences, often misunderstood or dismissed by employers. Post pandamic social anixiey amoungst the community is common. many people have now begun to devolop a stutter.

Natural Disasters and Unpredictable Circumstances

When bushfires ravaged parts of Australia, many, like Aiden, found themselves cut off from their daily routines. Roads were blocked, communication lines were down, and priorities shifted from work commitments to basic survival. (we have seen this in previous years with floods as well)

In the aftermath, while many returned to their jobs, some faced the unintended consequence of their forced absence: potential abandonment of employment concerns. Natural disasters, often unforeseeable and devastating, pose significant challenges for both employees and employers.

The Legal Landscape – Fair Work Act 2009

Notice and Final Pay

Fair Work Act is Section 117, which articulates the obligations tied to notice of termination and final pay. It clearly sets out the the dismissal of an employee has to be in writing. Before labelling an absence as abandonment of employment, employers must ensure that they’ve not prematurely reached conclusions without following due process.

Section 385 – Unfair Dismissal

A pivotal piece in the abandonment puzzle is Section 385. Herein, unfair dismissal is detailed, establishing the criteria that need to be met for a dismissal to be classified as ‘unfair.’

In the context of abandonment, this section underscores the imperative for employers to be thorough and diligent. Any premature or inadequately substantiated classification of abandonment can render the dismissal ‘unfair,’ leading to potential legal ramifications.

General Protections

Perhaps the most important part in relation to abandonment, Part 3-1 sets out the protections extended to employees during temporary absences. Especially relevant for situations borne out of illness, (sicknessinjury, or other unforeseen personal challenges, this part mandates that employees shouldn’t be dismissed for such reasons.

For employers, it emphasizes the significance of distinguishing between genuine, unavoidable absences and intentional abandonment, thereby ensuring that the law’s protective umbrella isn’t unjustly denied.

The Responsibilities of Employers

In the maze of regulations, codes, and corporate expectations, employers often find themselves balancing on the tightrope of operational needs and appearing to not engage in discriminatory behaviour. An unexplained absence, especially when extended, is undeniably disruptive. However, the law and company moral considerations dictate a course of action that isn’t purely reactionary.

The cornerstone of addressing potential abandonment scenarios is establishing communication channels. Reaching out to the employee, understanding the cause of their absence, and ensuring their well-being should be paramount. This not only aligns with the Act’s provisions but also reinforces an organizational culture of empathy.

Rushing to judgments is fraught with risks. Before proceeding with abandonment protocols, involving the HR department and legal teams is crucial. Their combined expertise can provide clarity, ensuring that decisions made are legally sound and humanely considerate. The case law states that Employers must make all reasonable attempts to contact the employee before dismissing them. Of course what is reasonble to one may nor be reasonble to another. It may depend on occupation, urgent company needs etc.

Noteworthy Legal Precedents

Doe vs. ABC Corp

In this case, Doe, who suffered from a rare medical condition, went missing for weeks. The employer, ABC Corp, proceeded to dismiss him on grounds of abandonment of employment. However, the Fair Work Commission ruled that the dismissal was unfair as ABC Corp had not made adequate attempts to understand Doe’s situation or contact him. This case underscored the importance of proactive communication from the employer’s side. Why not give the employee a fair go.

Smith vs. XYZ Enterprises

Here, Smith, faced with the sudden illness of a family member overseas, had to leave immediately, causing an extended absence. While XYZ Enterprises was initially unaware of the reason, they eventually learned of Smith’s predicament. However they still chose to dismiss him, they classified the absence as abandonment of employment. The Fair Work Commission referencing Part 3-1 of the Act, deemed this dismissal unjust, emphasizing the responsibility of employers to factor in genuine temporary absences.

Australia vs. what goes on elsewhere

Every nation, while dealing with abandonment of employment, offers a unique perspective. United States The U.S., largely operating on the ‘at-will’ employment doctrine, gives employers considerable leeway. (there are no unfair dismissal laws in the USA) However, certain state-specific mandates and federal provisions, like the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), act as protective shields for employees facing genuine absences. This particulary applies around discrimination reasons for dismissal

United Kingdom: The UK’s Employment Rights Act 1996 protects employees against unfair dismissal, much like Australia’s Fair Work Act. However, they differ, especially regarding the time frame constituting abandonment and the obligations of employers in such scenarios. Canada: Canada’s employment dynamics operate on a provincial basis. Yet, the overarching Canadian Labour Code provides some uniformity. The emphasis, much like in Australia, is on thorough investigations and ensuring that abandonment of employment dismissals only occur after all reaonsable attempts have been made to contact the employee.

The Path Forward: Recommendations for Employers and Lawmakers

Strengthening Communication Channels

Modern technology offers myriad ways to communicate, from emails and phone calls to wellness apps. Implementing these tools, especially during unexplained absences, can bridge communication gaps. Regular wellness checks can also be a vital protocol, showing employees that their well-being is a priority. Good employees want to work for good companies. Not ones with a toxic culture.

Legislative Revisions

The Fair Work Act, while comprehensive, can benefit from periodic revisions, especially in addressing the grey areas of abandonment of employment. Detailed guidelines on what constitutes “adequate efforts”or ‘reasonble attempts” to reach an absent employee or the introduction of mandatory welfare checks can add clarity. With an increased Gig economy and many employees working from home workplace laws have to reflect and consider the changes in society.

Creating Awareness

Companies, in collaboration with unions, can organize workshops underscoring the issues of abandonment of employment. Enlightening both employers and employees can foster a more understanding and empathetic workspace. The discourse around abandonment of employment isn’t merely about statutory compliance or operational efficacy. At its heart, it’s about humanity, empathy, and understanding. It’s about recognizing that every desk, every workstation, every role is occupied by humans with their set of challenges, dreams, and unpredictability’s.

Australia’s Fair Work Act managed by the Fair Work Commission has laid the foundation for a fair approach to the wiorkplace and dismissals. But the onus is on employers, employees, and goverment at large to build upon this foundation, ensuring that every story of absence is not just heard, but also felt and understood.

“Regrettable, expensive and damaging episode” Case Study

The FWC might refer a to the South Australian Correctional Services Department, after it failed to allow a employee on remand to contact his employer. In turn the employer dismissed him for failing to attend work. Spotless Services Australia Limited emailed the full-time security officer in April this year to tell him the company accepted his failure to attend six rostered shifts and to respond to its attempts to contact him, as him repudiating his employment contract.

Unbeknown to the Downer Group subsidiary, the South Australian police arrested and charged the security officer for a reason the Commission withheld, and held him in remand for 23 days. Then after all this, dropping the charges and releasing him. While in remand, the security officer “requested and was granted permission to speak by telephone to nominated friends but only those whose telephone numbers he knew”.

He could not access the internet or his mobile. The worker asked the department if he could contact Spotless Services, but when the remand centre released him, his request remained “pending”. Spotless Services tried to call the security officer each time he failed to attend a shift. After he failed to attend six shifts, the company emailed him to say it might consider his conduct abandonment of employment, which could lead to dismissal, and it invited him to respond.

Conduct repudiated his employment contract

The security officer failed to respond. In turn a week later, Spotless Services emailed him again, confirming that his conduct repudiated his employment contract, and the company had chosen to accept his repudiation. When South Australia police dropped the charges, the remand centre released the security officer. Upon his release, he “felt traumatised and unwell”. His phone and internet accounts were disconnected because he hadn’t paid his bills.

Nine days after his release, the security officer read the Spotless Services emails for the first time. He tried to call and text his manager, with no response. Two days later he emailed Spotless Services to explain his absence in detail. A HR advisor responded with a copy of the letter it previously sent him. Spotless Services didn’t respond to further contact attempts, so the security officer used a friend’s phone to call his manager. This was so that the manager wouldn’t recognise the number, but the conversation failed to reach a resolution.

Repudiation not a dismissal: Fair Work Deputy President rules

In finding that the security officer’s employment did not end “on the employer’s initiative” (under the Fair Work Act’s s386), Deputy President Peter Anderson considered that repudiation is “a question of fact not law”.

“I fully take into account that [the security officer] did not intend to fail to attend for work and that he made reasonable efforts when in remand to notify Spotless”.

Deputy President Anderson

“It was circumstance and not intent that gave rise to the breach of his obligation to turn up for work. “However, the question of whether there has been repudiation of a contract of employment is determined objectively. It is unnecessary to show a subjective intention to repudiate.” He found the security officer’s conduct repudiatory because “after an absence of six shifts, I am satisfied that the failure to attend for work as rostered so struck at the heart of [the security officer’s] employment obligations that it objectively signified an inability (although not an intention) to render substantial performance of the contract”.

He cited 2018 Abandonment of Employment decision, in which a full bench found “although it is the action of the employer in that situation which terminates the employment contract, the employment relationship is ended by the employee’s renunciation of the employment obligations”.

Deputy President Anderson found that in “applying the established approach, although it was the action of Spotless which terminated the employment contract with [the security officer], this was not a dismissal within the meaning of s386 because the employment relationship had by then already ended due to [the security officer’s] renunciation of his obligation to attend work when rostered”.

Post-dismissal conduct harsh, but alleged dismissal not unfair

DP Anderson considered the employer’s “dismissive attitude” toward the security officer when he tried to explain his absence from work “harsh”. “Whilst by then [the security officer] was no longer its employee, given the factually accurate story he described and his plea to be re-employed, he was simply re-sent the employer’s earlier letter advising repudiation; a letter which he had already read and which had been prepared without the benefit of the facts he was now trying to relay”, the deputy president said.

“[The security officer] was then left to use a friend’s phone so that his caller ID was not identifiable to trigger the conversation with his former manager that he had been seeking. “In that one and only conversation he was advised that he was wasting his time because the human resources department had made its decision. “Whilst this conduct was objectively harsh because it evidenced a closed mind to his re-employment plea, it was conduct after employment had ended and cannot characterise the alleged dismissal as unfair.”

DP Anderson considered that had it been necessary to determine whether the security officer’s dismissal was harsh, unjust or unreasonable, he would have found it fair. “Despite the alleged dismissal quite understandably appearing harsh to [the security officer] and having harsh consequences compounded by the employer’s uncooperative post-dismissal stance, the alleged dismissal was not, when objectively assessed, harsh, unjust or unreasonable”, he said.

Custodial authorities insensitive to workers request

DP Anderson considered the alleged dismissal “rationally based but which was regrettable”, and a “fortuitously rare case” in which neither the worker nor the employer’s fault led to his employment ending. He observed that the evidence “suggested a less than acceptable level of sensitivity by custodial authorities” to the circumstances of a worker placed in remand trying to explain their absence from work or “salvage their job”.

He found that the remand centre’s conduct in leaving the security officer’s request to contact his employer “‘pending’ for a prolonged period”, resulted in “regrettable consequences”. In that the security officer losing his job, and the cost to the business, which double-rostered during his absence. DP Anderson said that consistent with the fairness objectives in part 3-2 of the Fair Work Act, “decisions about ending employment relationships to be made with as accurate and timely information as possible”.

He suggested that in future correctional services should ask people it takes into remand:

- Do you have a job?

- Does your employer need to know that you are in custody?

- If so, can we take steps to inform your employer or help you do so?

“Had those questions been asked of [the security officer] at the outset this regrettable, expensive and damaging episode would likely have been avoided”, he said. Deputy President Anderson asked the Commission’s general manager to refer his findings and observations to the South Australian Department for Correctional Services’ chief executive, and noted that “they may also be of interest to other custodial authorities”.

Muhammad Ali Qureshi v Spotless Services Australia Limited [2023] FWC 2411 (19 September 2023)

Recommendations and Conclusion to: Abandonment of employment that went wrong

As the corporate world becomes increasingly complex, intertwined with the unpredictability’s of human experiences, the concept of abandonment of employment will need continuous revaluation. While the Fair Work Act 2009 provides the legal scaffold, it’s upon employers and goverment as part of a holistic approach to the workplace to do better.

For every unexplained absence, there’s a story. It could be one of tragedy, medical challenges, or unforeseen circumstances. Or it could be just an excuse and these employees need to be disciplined or dismissed. By understanding and addressing these stories, Australia’s workplaces can ensure that genuine employee’s plight remains heard or not misunderstood.

Call 1800 333 666 for prompt, confidential advice.